The car finance scandal could have ended up costing UK banks and lenders up to £44 billion in compensation payments. But after the latest court ruling, the expected bill has been reduced to less than £18 billion.

That still counts as an expensive loss of course. And it may or may not be enough to compensate the millions of motorists thought to have paid more than they needed to for car loans.

But as well as the financial hit taken by both sides, the whole affair has come at a great cost to the relationship between the public and the financial sector. An industry still grappling with trust issues has once again been accused of long-standing practices that cost consumers dear.

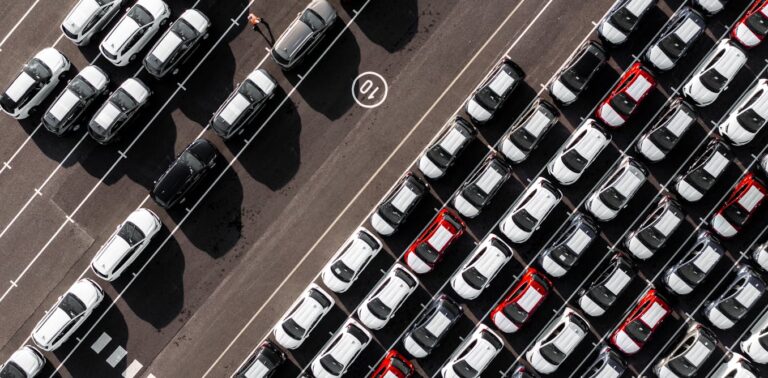

Under the now-banned “discretionary commission arrangements”, car brokers were allowed to increase the interest rate on car finance agreements and receive higher commissions as a result. But customers weren’t necessarily told this at the time, and the deal may have seemed like a standard finance agreement.

The practice was widespread until 2021, when it was banned by the UK’s financial services regulator. Before that, consumers were often unaware that brokers had both the power – and incentive – to manipulate the cost of their borrowing.

The result is that millions may have overpaid for car loans, sometimes by thousands of pounds, without ever knowing. While the Supreme Court has now clarified the legal boundaries of the case, the fact that such practices were widespread for years raises serious ethical concerns.

For the scandal is yet another reminder of the fragile relationship between financial institutions and their customers. Most people might expect that loan agreements will reflect market conditions – rather than be at the discretion of a salesperson keen to maximise their own commission.

Research shows that trust is fundamental to the proper functioning of financial markets. In financial services, it depends on transparency, fairness and clear communication.

Discretionary commission arrangements violated all three of these concepts.

In some ways, the case bears similarities to the payment protection insurance (PPI) scandal, where customers were sold policies designed to step in if they were unable to repay loans because of unemployment or illness for example.

Both PPI and the car loans involved financial products being sold under conditions that consumers might not have fully understood, and both relied on misaligned incentives between lenders and borrowers. They also both exposed how a lack of transparency can lead to large-scale consumer harm.

Yet in the case of car finance, the court did not order compensation for the majority of affected borrowers. One claimant won his case, but the court stopped short of declaring all such commission arrangements unlawful by default.

Nonetheless, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the financial regulator, has launched a review into historical car finance commission practices….

Read More: The car finance scandal proves that the financial sector still has trust