Luiza Januário argues that the threats and opportunities of nuclear technology are an intrinsically global matter. Here, she offers a South American perspective on the nuclear politics dilemma

An unfair global nuclear order

As the nuclear era dawned, states were forced to update their strategies on dissuasion and arms control. But their new strategies didn’t just affect potential nuclear powers and their close allies. Nuclear politics, including the peaceful use of nuclear technology and the danger represented by its military use, affects every country in the world. Despite this, political organisations and academic research overlook the nuclear experiences and expectations of many states, particularly those in the Global South.

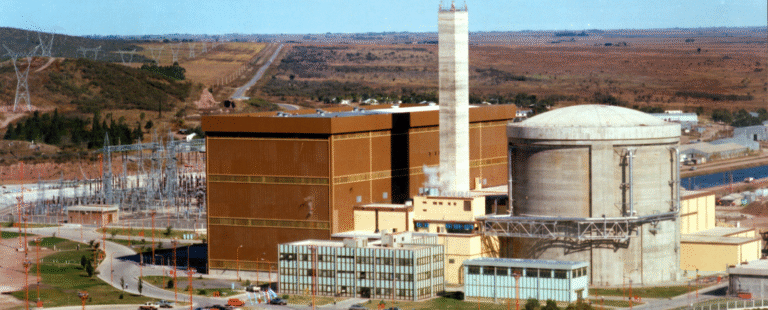

For most of the developing world, nuclear politics is not simply a matter of security. It is also one of development. This is central to nuclear politics in South America, particularly for Argentina and Brazil, which developed the region’s most advanced nuclear programmes. For South America, nuclear technology represented modernisation and scientific innovation, social and economic development, and a passport to the big boys’ club of international politics.

For developing countries in South America, nuclear technology represented a passport to the big boys’ club of international politics

The nonproliferation regime centres on the discriminatory principle of the nuclear haves and have-nots of the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). But the NPT’s hierarchy hinders the ambitions of developing countries. It is crucial that we achieve justice for such countries, particularly when many are questioning the value of nonproliferation. Considering the viewpoints of marginalised communities may constructively inform nuclear policy.

Original and legitimate solutions: a regional approach

South American and Latin American nuclear states sought innovative solutions to overcome local concerns about the nonproliferation regime. The best-known initiative is the Treaty of Tlatelolco. Opened for signatures in 1967, it established the first nuclear-weapons-free-zone (NWFZ) in a densely inhabited area. This set the precedent for similar arrangements in other parts of the world, and created a regional face for the nonproliferation norm.

Its approach remains relevant today, as attested by the ongoing debate about a NWFZ in the Middle East, which some experts suggest may offer security without nuclear weapons. Legitimacy is central to the Latin American and Caribbean NWFZ.

The Treaty of Tlatelolco, opened for signatures in 1967, remains a valid and original agreement for dealing with the dangers of the nuclear age

The Treaty of Tlatelolco remains a valid and original agreement for dealing with the dangers of the nuclear age. Even during the decades when the Brazilian government was cautious about nonproliferation initiatives, it considered Tlatelolco a force for good, in contrast with the…

Read More: South America’s plea for diverse perspectives on nuclear politics